In this article:

The good news based on our test experience: many production fins fit well with freeride boards and offer solid performance. However, this only applies if you are a typical average surfer. If you weigh between 70 and 90 kilos and ride the sail sizes recommended for the board in question, you'll be fine. However, if you don't have an XL fleet and want to use your freeride board in very light or strong winds, you can massively expand the range of use with an additional fin. The same applies to lightweights or surfers who weigh a few kilos more.

"A second fin expands the range of use - similar to an additional sail size." - Stephan Gölnitz, surf editor

Here we tell you all the basics about fins, function, the right size and typical mistakes when buying a fin.

How the fin works

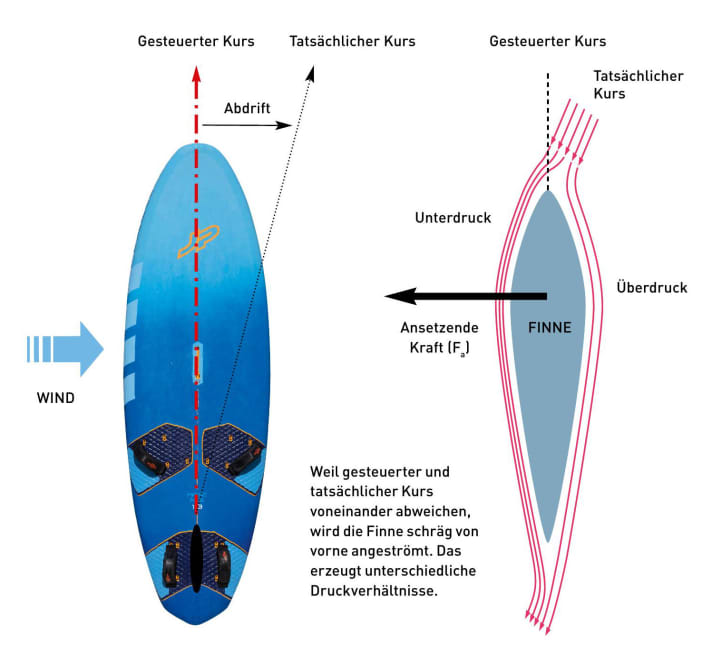

The fin ensures directional stability and is, to a certain extent, the motor of the board. When travelling in a straight line, however, the fin does not receive a direct flow from the front, as the board does not travel exactly in the direction of the chosen course, but slightly offset. The reason for this is the lateral drift. This leads to overpressure on the leeward side of the fin and underpressure on the windward side (see graphic below).

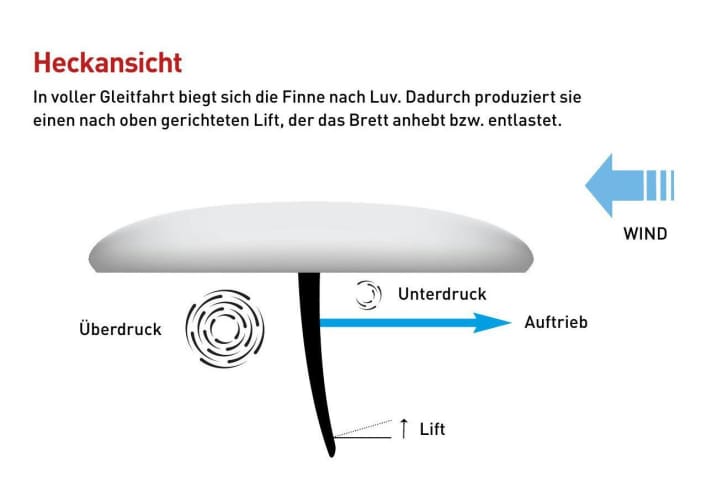

In addition, the thin and soft fin tip bends slightly under water. When fully planing, it is therefore not straight as a die under the board, but is bent slightly in a crescent shape towards the windward side. The force applied to the fin (Fa) therefore not only acts in the direction of the negative pressure on the upwind side, but also upwards. This causes the upwind edge of the board to lift.

If you want to freeride sportily and ride at high top speeds, you can take advantage of this by deliberately placing the board slightly on the leeward edge. As a result, the fin generates more lift, the board becomes freer - and also faster in the ideal wind range. The fact that this force does not cause the board to capsize is due to the stance position. With freeride boards, this is not centred over the centre of the board, but offset to the outside. This means that the wider the tail of the board is and the further out the straps are mounted, the more force you can exert against the lift of the fin.

The tail width, strap position and fin length must therefore be harmonised. Ideally, the buoyancy of the fin lifts the upwind edge of the board slightly when planing, so that the board glides freely over the chop.

Example 1: fin too large

The longer the fin, the greater its buoyancy and thus the capsize moment. If you are travelling with a fin that is too long, you will feel this when planing due to increasing pressure on the back leg. If a gust is added to this or the course changes to a closehauled course, the fin's lift can no longer be tamed. The windward edge rises uncontrollably - and a wheelie is the result.

Example 2: fin too small

If you surf with a fin that is too short, it cannot produce enough lift due to its short length to lift the upwind edge of the board slightly when planing. In a way, you are then surfing on the windward edge through the water. This is problematic, because the upwind edge then enters hard into every chop, which limits riding comfort and speed. Performance is also reduced when planing and travelling through wind holes - so you start planing later and park again more quickly.

Spin-outs: causes and countermeasures

The term spin-out refers to an uncontrolled stall at the fin. The tail then slides sideways in an uncontrolled manner - and the planing comes to an abrupt end. The most common causes of spin-outs are load errors, often as a result of incorrect sail trim. However, a fin that is too small can also be the reason for frequent spin-outs, as small fins cannot withstand the strong lateral pressure of the rider, especially when travelling upwind. If you often have to deal with spin-outs during a session, you should fit a slightly larger fin and try not to put too much pressure on the tail when going upwind. Fins with thicker profiles also help as they are more stable in the airflow.

Fin profiles

The profile describes the thickness of the fin. Similar to an aeroplane wing, a fin is thicker in the middle area than at the leading and trailing edges. As a rule, the thickest point is in the front third - designers rack their brains every day about where exactly the thickest point of a fin should be. In general, the following principles apply to fin profiles:

Thick profiles offer

more lift, i.e. more power when planing

More stable flow in the event of load errors, i.e. less susceptibility to spin-outs

better uphill running

higher driving resistance - and thus a lower top speed on a space wind course

Many standard freeride board fins are compromise solutions in terms of their profile, designed to combine planing power, a stable inflow and a good level of speed.

Flex & and materials used

Fin designers have the opportunity to massively influence the riding characteristics, particularly via the flex. How much a fin flexes at certain points is influenced by the profile thickness, the material used and the arrangement of the individual layers. Here is an overview of the most common materials and their properties:

G10 fins

G10 consists of GRP sheets pressed under high pressure. Individual layers are not recognisable here, the material is very dense. The fin profiles are milled out of these sheets. G10, which often looks yellowish or greenish in colour, is considered robust, can be sanded well and is comparatively stiff. This is why many manufacturers equip their freeride and freerace boards with G10 fins. However, designers can only control the stiffness and flex of this material via the thickness of the profile. This limits the options for designers, which is why G10 is rarely used for high-end slalom or race fins.

GRP fins

Here, glass fibre layers are placed in a mould, impregnated with resin and then baked. This means that individual layers remain recognisable. GRP fins are lightweight, and the flex and profile can be controlled by the arrangement of the individual layers. Disadvantage: GRP fins are less robust in the event of stone contact and can burst open, making repairs more complex.

Carbon sandwich fins

Here too, individual layers are bonded in a mould with the addition of epoxy resin. Compared to normal glass fibre material, however, carbon is very stiff. This means that thin (and therefore fast) profiles can also be realised - without the fin becoming soft like rubber and bending too much. Because the arrangement of the carbon fibre layers allows the stiffness and twist to be precisely controlled, carbon is mainly used for slalom and racing fins. Disadvantages: The noble carbon fins do not like stone contact at all, and the prices are significantly higher than for G10 or GRP.

Box systems

The system most commonly used in the freeride and freerace sector is the Powerbox. The position of the fin is fixed and it is connected with a screw from above through the deck. This is quick and offers the best ease of use. For reasons of durability, the Powerbox is only used for fins up to around 50 centimetres in length. Sporty freerace or small slalom boards are often equipped with a tuttle box. Here, the fin also sits in a predefined position, but is connected from above through the deck with two screws. For large slalom boards, which have a wide tail and therefore require a long fin, the tuttle box becomes the deep tuttle box. This deeper box offers a larger mounting surface and is more stable due to better force distribution.

The right fin length

The question of the right fin length remains. Which length makes sense depends on body weight, sail size, tail width and, last but not least, the conditions. Our years of testing experience have shown that manufacturers consistently equip their freeride and freerace boards with quite generous fin lengths, because the longer the fin, the easier it is to planing, gliding through wind holes and going upwind. So if you buy a board, you will usually also get a suitable standard fin for the normal wind range. If no fin is included when you buy a board - and if you can't find any information about the length of the standard fin, a small rule of thumb can help: Normally, the maximum sensible fin length corresponds to the tail width of the board in front of the fin box, the so-called one-foot-off measurement, i.e. the width at about 30 centimetres from the tail.

The standard fins can naturally only cover one core area of use. A second fin makes sense, especially if you have a limited board fleet and want to expand the range of use of your board for a reasonable investment.

"Buying a good fin is the cheapest way to expand your riding fun and range of use." - Manuel Vogel, surf editor

Extra power for jumbos

If you weigh over 90 kilos and naturally ride larger sails than average, you will sometimes reach the limit with the standard fins. To improve planing and glide and reduce the risk of spin-outs with large sails and when going upwind, it makes sense to use an alternative fin that is three to five centimetres longer than the standard fin. Those who like to ride long strokes and want to pull a lot of height will benefit from longer fins.

Small fins as a strong wind supplement

Conversely, using a smaller fin can make just as much sense. For example, most freeride boards with 130 to 150 litres are optimised for sail sizes between six and nine square metres. If you mainly use these sail sizes, you don't have the ideal board fin setup for the few windy days on which the 4.7 litre is rigged. To prevent the tame freeride board from mutating into a wild stallion, the fin needs to be swapped. If you switch from a 46 to a 40 fin, for example, you will be able to ride in a controlled manner even when hacking - and also achieve a significantly higher top speed. In general, a fin length reduced by four to eight centimetres compared to the standard fin is a good measure for strong winds.

The Ijsselmeer problem

In many inland areas of Europe, the focus is on completely different problems. On the Ijsselmeer & Co. it's not about which fin length you can use to get a little more performance on the cross, but simply about the question of which fin still works passably in knee-deep water. If you need to reduce the draught, you have to decide whether to use short standard fins, weed fins or special shallow-water fins.

Standard, seagrass or delta fins?

Of all the options, using a short standard fin is the worst. If you want/need to ride a freeride board with a 46 mm standard fin in knee-deep water, you can't simply screw in a 30 mm standard fin. The consequences would not only be poor planing and levelling, but above all extreme susceptibility to spin-outs. The reason for this is that there is simply not enough surface area to withstand the pressure exerted on the tail.

For this reason, many surfers opt for weed fins in shallow inland areas. These also have a significantly reduced draught, but a lot of surface area. Timm-Daniel Köpke from Maui Ultra Fins explains the correlation: "If you screw in a 38 standard fin instead of a 46 series fin, you have saved eight centimetres of draft, but the fin also has 20 to 30 percent less surface area. If you fit a 38 weed fin instead of the 46, for example, the draft is also reduced - but the surface area is even 20 per cent larger compared to the long 46 standard fin. This is particularly helpful in preventing spin-outs. Although you can't sail at quite the same angle to the wind when going upwind, you can at least put a lot of pressure on the tail and go upwind without the tail slipping away. Weed fins are generally a little less efficient and therefore require more surface area."

But what if the water depth is even shallower? Then the so-called delta fins are the best and only option. The basic idea: maximum surface area with minimum draught. Timm-Daniel Köpke advises: "If even the 38 mm weed fin is still too long, a Delta-XT-50 is also possible. This only has a draught of 28 centimetres, but almost 50 percent more surface area than a standard 46 mm straight fin, for example. The delta fins work ideally on smooth water and in a roomy wind. However, the water behaviour of the board is noticeably smoother. I would therefore recommend the following adjustments with seagrass or delta fins:

- Adjust the boom two to three centimetres higher

- Harness lines slightly longer

- Push base plate backwards

- Foot straps one position further back These measures allow the board to move a little more freely."