With a little favour, foils can be seen as the invention of the wheel on the water: More efficient and faster than any glider - the same speeds can be achieved with much less energy. The gigantic 50-foot foil catamarans in the SailGP class can reach a top speed of 32 knots (59 km/h) in seven to nine knots of wind - four times the wind speed. Windsurfers can also break the 40 km/h mark with a freerace foil set in around 15 knots of wind. With normal fin freeride material, you are still struggling to glide in this wind range. But regardless of whether you're using high-tech offshore equipment costing millions - a foil set alone can cost that much in the SailGP - or an aluminium foil on a normal freerace board, everyone is basically equal when it comes to the laws of physics.

Windsurfing foil - the magical balance

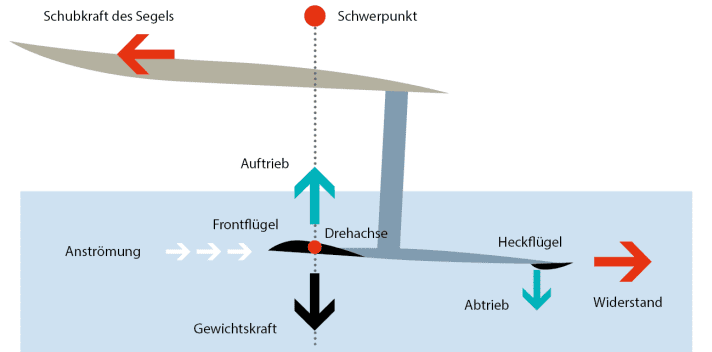

Seen from the side, a foil windsurfer looks like an optical illusion. The board, surfer and rig are balanced on the foil mast, which seems to protrude far too far back into the water: why doesn't it all just tip forwards? The apparent trick is based on two components: Firstly, the weight of the surfer, rig and board is actually concentrated further back than the visual impression would have you believe, namely just behind the front foot straps. Just below this, the front wing - offset forwards from the foil mast - carries the entire load through its dynamic lift (graphic, page 25). Also invisible, the second wing performs its task far behind the board under water. The back wing, also known as the stabiliser, constantly pulls downwards due to its angle of attack and prevents the sail thrust from pushing the bow into the water. An extremely delicate balance that requires constant, delicate weight shifts.

If the nose rises, the upper body swings slightly forwards to compensate and vice versa. With increasing practice, the deflections become smaller and the flight more and more stable, and the changes in load can no longer be seen from the outside. Windsurfing and wing foiling are the most favourable, but also the most technically simple forms of foiling. In other foil classes, sophisticated constructions with movable, adjustable foils take over the trim in the longitudinal axis.

Nothing is fixed - how the moth works

Like the needle of a record player, the movable sensor on the bow of a "Moth" scans the surface of the water (picture above). It registers the quiet passages in the almost smooth water as well as the crescendo when the Moth flies over large choppy waves at full speed. Each deflection is transmitted to the main foil via an intricate system of rods. In terms of flight altitude, the push button sets the tone. As with an aeroplane, the rear part of the main wing is designed as a movable flap that is permanently hinged by the linkage.

As the boat rises, the angle of attack is automatically reduced and the lift decreases until the foil is even programmed for downforce just below the water surface. So there is no chance of a spontaneous dolphin jump out of the water, which windsurfing foilers like to celebrate when the foil catapults into the air with full lift until it surfaces. "The range between maximum lift and even downforce can be adjusted before the start, depending on the conditions, and the right setting prevents this from happening," explains Moth sailor Max Gasser from the YACHT editorial team.

The rear wing of the moth is also adjustable

"The mechanics on the rear wing are much simpler. There is no movable "flap" on the rear foil like on the main wing, but you can tilt the rudder with the fixed rudder foil by turning the tiller. With five to ten turns, depending on the thread installed, the angle of attack of the back wing can be very finely adjusted. This allows the bow to fly higher or lower, depending on the course."

Moth sailors try to fly as high as possible overall, because "the flight is more stable and the drag is lower because the profile (ed.: of the foil mast) is thinner at the bottom and there is less surface area in the water," adds Max. The adjustable length of the sensor makes it possible to set the optimum flight altitude for different conditions.

Compared to so many adjusting screws, a windsurfing set that is controlled solely by shifting weight is like a wheel next to an MTB with electric gears. As a consolation, you can work out how many windsurfing days (including equipment) can be financed with the price of a Moth - new price from around 30,000 euros. Despite so much technical support, Moth sailors are certainly not passive co-passengers; the class is one of the most demanding foil boats.

SailGP soon with "windsurfing foils"?

In the undisputed Formula 1 class of sailing, problems are being solved that we windsurfers would like to have. Foil catamarans in the F-50 class are currently experimenting with T-foils because cavitation (formation of vapour bubbles along the profile) is causing problems with conventional J-foils at the 100 km/h mark. Instead of being laminated from carbon, foils are milled from titanium, which is already being experimented with in the Moth Class. The highest measured top speed of an F-50 foil catamaran is currently 99.94 km/h, and with T-foils even 110 km/h should soon be possible. This also brings the Vestas Sailrocket 2's absolute sailing speed record of 65.45 knots (121 km/h) a little closer. Because the racing catamarans fly completely free on the foils, the angle of attack of the back wings is set perfectly every second by a crew member as a full-time job. One-handed world circumnavigators like Boris Herrmann don't have a free hand for this.

Imoca Open 60: Foil flight around the globe

In the Vendée Globe, the single-handed sailing race around the world, he and his fellow competitors sit in ships that could make you feel like you've landed in the cockpit of a DC-10 on the water. They navigate from the command post in the hull, operating the sails and calculating courses and settings. However, the sheer amount of ropes and technical equipment that converge here do not control the trim of the boat to the same extent as it is permanently controlled with the foil angles on the F50 catamarans. The foil shape used here has a self-stabilising effect.

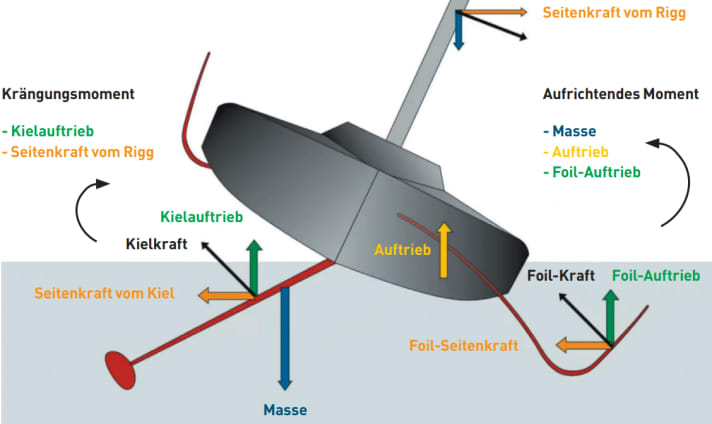

These ships in the Imoca 60-foot class, such as Boris Herrmann's "Malizia - Seaexplorer" (above), use so-called L- or J-foils. These curved foils never lift the ship completely out of the water because the shape of the foil automatically reduces buoyancy the higher the foil rises out of the water. This causes the boat to sink again, which in turn increases the buoyancy - and the foil equilibrium stabilises. The hull is therefore more in a kind of "hyper-glide state" on a minimal gliding surface than in a completely free foil flight. Accordingly, no further foils are provided on the control surface for stabilisation.

J- or L-Foils let the Imocas fly

However, even when foiling autonomously, single-handed sailors cannot sleep without worry. "In the worst case scenario, a boat like this can tip forwards," says Max Gasser from YACHT magazine. "During the last Vendée Globe, one of the Imoca 60-foot foilers crashed from one wave into the next. This resulted in a reverse load on the foil, so that the foil actually worked negatively and pulled the bow even further into the wave. The ship then broke apart in the middle." Around six million euros can be sunk in a nose dive like this. No wonder that even the best professional sailors like Boris Herrmann or Erik Heil get on a wing foil board from time to time. Together with the windsurfing foil, this is the foil class in which you can simply push the boundaries - because in the event of a fall, you can make the cheapest take-offs.