Dr Watermann, 21 years ago, the countries bordering the Baltic Sea set themselves the goal of restoring it to a near-natural state by 2022. Has this been achieved to some extent?

Dr Burkard Watermann: No! The Baltic Sea is a long way from achieving these goals. A very large group of researchers recently compiled a "Baltic Sea Health Index" to document the status of efforts in many areas. The agreed natural state would be 100 on a scale; after analysing the data, it stands at around 75 percent on average. As I said, on average. There are regions that are at 40 per cent. And there are also clear deteriorations in many areas.

For example?

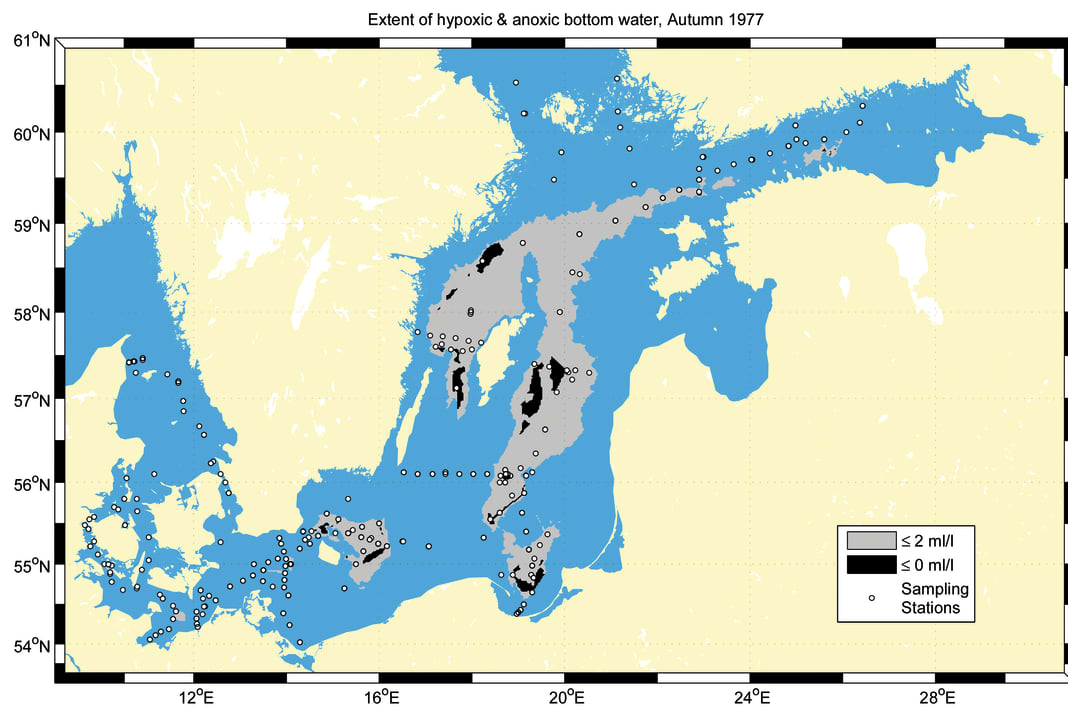

For example, the oxygen-free dead zones at the bottom of the Baltic Sea are expanding considerably. This is a consequence of far too much eutrophication, i.e. too much nutrient input into the Baltic Sea. This is mainly phosphate from agriculture and factory farming. There is still a lack of really good sewage treatment plants for municipal wastewater, although there has been great progress in this area in recent decades. We are a long way from achieving any real improvement in this important area in particular.

To what extent is climate change affecting the Baltic Sea?

The Baltic Sea is one of the marginal seas that has warmed the most in the last ten years. It is already at around 0.6 degrees. That is quite considerable. It reinforces the famous chain: nutrient input, plankton bloom, plankton dies, sinks to the bottom, where an oxygen deficit develops. You can look at Lake Constance as an example. It was also extremely overloaded with nutrients, and it was only through sewage treatment plants and bans that a turnaround was achieved after around 20 years.

Far too warm: the water temperature is rising continuously

But what would have to happen for the Baltic Sea to experience a turnaround like Lake Constance?

In agriculture, the decisive step would be to move towards organic farming with a much lower use of fertilisers and a move away from factory farming. At the moment, the liquid manure used as fertiliser is spread on the fields and washed into the Baltic Sea as a result of surface run-off from the rain.

So there is no improvement in sight? Germany is still a long way from a widespread switch to organic farming, with the rate in the north-west at around seven per cent and in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania at 14 per cent.

The Swedes and Danes are actually further ahead than Germany in this respect. The proportion of organic food there is significantly higher and is also growing faster than in Germany. Nevertheless, too little is happening overall to bring about an improvement. And climate change is also working against it at the same time.

Eutrophication is therefore one major, if not the biggest problem. What else is causing problems for the Baltic Sea?

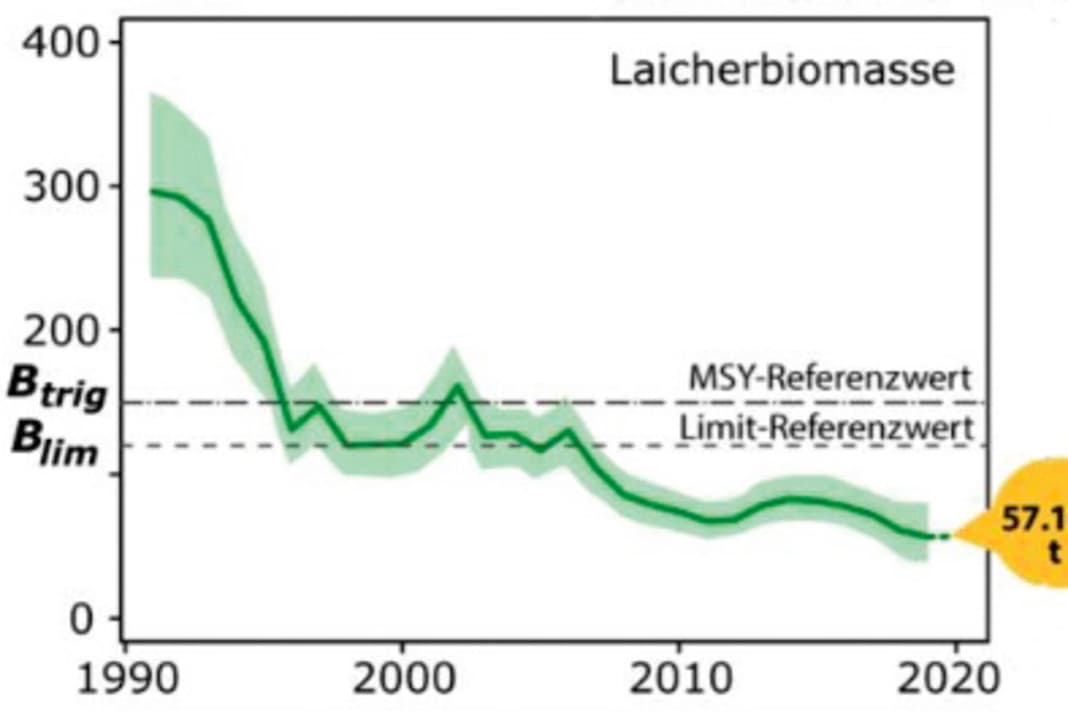

Figuratively speaking, some animal and plant species are caught in several traps at once: In addition to the nutrient and climate trap, there is also the fishing trap. A good example of this is the herring. They usually spawn in the Greifswalder Bodden and the surrounding area. The animals come there from the Øresund. However, due to the rise in temperatures, they now swim off earlier and spawn earlier than ever before. As a result, the young hatch before there is enough zooplankton available. This is because zooplankton does not thrive depending on the water temperature, but on the length of the day, i.e. the hours of light. The result: the herring offspring starve to death. Even those animals that hatch a little later are in danger. Many die as a result of cardiac arrhythmia because the water is too warm for them. This means that the offspring of the herring off our coast are extremely endangered.

Just like the cod?

Yes, cod lay their eggs on the bottom. But because there are ever larger areas without oxygen at the bottom, the larvae die. The Thünen Institute of Baltic Sea Fisheries and Geomar in Kiel have therefore been calling for a drastic reduction in catch quotas for years. There are very, very detailed scientific studies on this. Nevertheless, catches are not being reduced accordingly because fishermen want to protect themselves from economic losses.

The inflow of North Sea water has always been important for the oxygen content of the Baltic Sea. Has anything changed in this respect?

The inflow of North Sea water, which is rich in oxygen and salt, has been decreasing in the winter months for many years. The simultaneous increase in nutrients in the water means that dying plankton blooms sink to the bottom in far greater numbers and cause oxygen depletion. The death zones that have long been observed at the bottom of the Baltic Sea, where there is no more oxygen and all life dies off, are unfortunately continuing to spread.

Dead zones at the bottom: The Baltic Sea is running out of air to breathe

Wasn't there an announcement three or four years ago that fisheries would in future be regulated by the supervisory authorities on the basis of scientific criteria?

Yes, there was a declaration of intent from the authorities, but it was simply not implemented. Yet herring is the fishermen's bread-and-butter fish, especially in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. If they lose it completely, then there will be real hardship on the coast. The Baltic Sea research institutes involved in the issue agree that a coordinated campaign by all Baltic Sea and North Sea countries to adjust fishing quotas could still turn the tide. However, if everything remains as it is, we are heading towards a catastrophe for fishing.

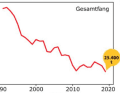

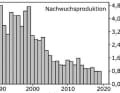

By what percentage have cod and herring stocks declined?

The herring catch fell by around 75 per cent between 2000 and 2019. Worse, however, is the decline in herring recruitment, i.e. the number of young fish that follow. Here we are almost at zero. That's very, very drastic! In the case of cod, too, the rate is down to around ten per cent of the original offspring. That is frightening!

Environmental indicator herring: if the Baltic Sea is doing badly, fish stocks suffer

How does this affect the harbour porpoise? They also live off these fish.

The harbour porpoise occurs in the Baltic Sea in two relatively strictly separated populations: one in the western Baltic Sea and the other in the central Baltic Sea in the waters around Rügen. The population in the west more or less maintains its population, but researchers are not in complete agreement. In the central Baltic Sea, however, including the coast of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, the harbour porpoise population is clearly in decline. At the moment, the harbour porpoises are still benefiting from the extreme reduction in cod stocks because they can now switch to its food, for example sprats. But they also have to adapt because they can hardly eat cod anymore and have to switch to smaller fish instead. Everything is very much interlinked. One encouraging sign, however, is that the Swedes want to establish a protected area for the whale between Gotland and Öland. It seems to be reproducing in large numbers there.

Are there any current harbour porpoise counts?

We have the fortunate situation that the Stralsund Oceanographic Museum now has an app that allows water sports enthusiasts to easily report sightings of whales and seals, including photos. Thanks to this and the counting of whale sounds, which are recorded using underwater microphones, the Oceanographic Museum has obtained an incredible amount of data. We are talking about over 2,000 data sets that could only have been collected otherwise at enormous financial expense. We can therefore only encourage all water sports enthusiasts to report their sightings in order to continue to improve the data situation. This will not save the harbour porpoises, but at least we will know what their situation is. After all, there are only around 500 animals left in the central Baltic Sea.

One of the few positive reports has to do with the seals. There are said to be almost 24,000 of them in the entire Baltic Sea after they were almost wiped out.

Yes, that's right, the grey seals in the Gulf of Bothnia have also recovered very well. This can now be seen even on the German coast, especially in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. However, the animals naturally have to feed themselves, so they are now becoming food competitors for the harbour porpoises. Fortunately, seals also resort to other fish species, such as flatfish. Their population is still holding up quite well. In short, there has been a pleasing increase in the number of seals.

According to her, the most important ways out of the dilemma would be for agriculture to reduce its nutrient inputs into the water and for fisheries to reduce their catch quotas. Instead, there is currently a huge debate about a new Baltic Sea National Park along the coast of Schleswig-Holstein. Isn't that just window dressing?

Theoretically, the national park should establish protected zones in which fishing is no longer permitted. This means that the fishing pressure is completely removed from small areas. This naturally meets with great resistance from fishermen. They say that's not possible because that's where our fishing grounds are. That is why there is a very extensive discussion about other fishing methods. Bycatch is also a major problem. An enormous number of fish are killed in the nets that are not wanted because they are far too small. That means not always just talking about the mesh size of the nets, but also replacing them with longline fishing or fish traps that are more selective. If the use of trawls were reduced in this way, fishing pressure could be countered much more effectively. A certain catch quota would still remain. Many research institutes are now calling for such a solution.

More gentle fishing methods would help fish stocks more than new, small-scale protection zones off the coast"

It would be relatively easy for the EU or the German government to control such a project. Why is it failing?

The resistance is very great. Bottom trawling and gillnet fishing are well established and the cutters are geared towards them. They would all have to be converted. This is a discussion in which some people realise and say that we have to change in order not to go under. Others, on the other hand, wave it off and think it's all exaggerated. It's like climate change: it can take time to accept that it's here. In the meantime, we risk passing the tipping points after which there is no turning back.

What does that mean in relation to the national park plans?

The path to a national park must be a transparent process and not a decision made by working groups behind closed doors: there must be open discussion events, otherwise it won't work. We can learn a lot from the Dutch or Sweden in this respect. It works better there, and public acceptance is also higher afterwards. But I have very good contacts in the ministry. From what I hear, they understand that there can't be any decisions made behind closed doors that offend people. On the other hand, it is clear that we have to do something for the Baltic Sea.

What specifically can we do as water sports enthusiasts?

For example, don't eat fish that are highly endangered. Cod should be left out for the time being so that the general demand for it decreases. Another important point, although more interesting for motorboat drivers: pay attention to the speed limit! Motorboats make an insane amount of noise under water at speeds of ten knots or more. This is often underestimated. However, the noise has been proven to disturb harbour porpoises, among others.

Doesn't that apply even more to the construction of wind turbines?

Correct, the pile-driving work required for this is sometimes very loud. This has already been recognised as a problem. There are now rules that ring-shaped dampers are placed on the pile driver during the pile-driving work, which reduce noise emissions by up to 30 per cent. That gives us hope. Marine biologists and we are now being consulted more frequently before such large construction projects. The construction companies and engineers cannot possibly be aware of all the problems that their work will cause for the environment. By contrast, entire construction phases can even be postponed if they jeopardise the reproduction of a species at a certain point in time.

The topic of the Baltic Sea and the environment seems to be a very difficult one. Apparently not much progress is being made. Isn't that frustrating for you as a researcher? Or are the recent protests by young environmental activists getting things moving after all?

You're right, it is very frustrating. Because the problems are not getting less, but more. We notice this, for example, in the fouling atlas that we compile for the Federal Environment Agency. For example, the Australian coral worm has suddenly appeared. It is now causing completely new problems. At first it was only found on the west coast, but now it has appeared on the Warnow in Rostock, presumably introduced by commercial vessels. It multiplies rapidly and clogs the cooling slots of engines, for example. I have already seen Z-drives where the propeller was actually a single coral ball after one season. The worm loves brackish water and has reproduced marvellously in the lower Warnow. Nobody can say what other invasive species we will get. That's not nice, of course. It's just not the case that after 20 years of research we have a solution and that's it.

So the only winners benefiting from the increased growth of algae in the Baltic Sea are the jellyfish?

Of course, they are happy about the many nutrients, the increase in plankton and they have less and less competition from juvenile fish. As long as the fish stocks do not recover and the nutrient input is reduced, I fear that the jellyfish will not decrease.

You yourself are a sailor and boat owner with a mooring on the Baltic Sea. Is it still possible to switch off while sailing with all that knowledge?

Yes, yes, it's still a lot of fun! I realise that the more I read scientific publications that highlight new problems, the more I need it. The crazy thing is, when I sail out onto the Baltic Sea, a lot of worries and thoughts stay in the harbour. I think that's exactly what you need to regain your strength. It's not an escape, you always come back. But you come back stronger. This effect should not be underestimated, I realise that more and more.

Dr Burkard Watermann

The marine biologist runs the private research institute LimnoMar - Laboratory for Limnic, Marine Research and Comparative Pathology in Hamburg. In particular, he has been studying the effects of recreational and commercial shipping on inland and coastal waters for 30 years.

- Further information at limnomar.de