In this article:

More second-hand guides:

The purchase of a second-hand sail is more expensive than the Board a simple matter? Because defects are more difficult to overlook here? That may be true, but what about the masts? One thing is certain: an older sail with a suitable mast that is appropriate for your sailing style, level, size and weight will always be more fun on the water than a brand new sail of the wrong class or size (in extreme cases with unsuitable components). There is no doubt that buying the right rig can be a science - the many brands with even more models quickly leave you with a head full of question marks.

In part two of our used market series, we therefore want to guide you through the typical route to finding the right sail and mast. In part three of the guide, we will then move on to the other components such as booms and extensions. Here too, we start with the question of which class or size makes sense at all - and how to recognise which sail class it belongs to and which masts will fit based on the characteristics of a sail. We then show you which areas you should pay particular attention to when buying a sail. And finally, we'll take a look at the current second-hand market and show you not only how to find used equipment - but also what the sails and masts currently (may) cost.

When buying second-hand, it is not necessarily the age of the sail that matters, but how much sun, sand and salt it has seen.

For example, if you are looking for a sail in 6.2 square metres, you can get everything from large wave and freestyle sails to freemove and freeride to small camber race sails on the second-hand market. This means you can quickly buy the size you want, but in the worst case, you'll end up with the completely wrong class, which is unsuitable for your needs. The same applies to the masts - the length is clear, but what do SDM, RDM and the different bending curves mean? If you know a few basics, you can find your way through the jungle of products on offer and avoid making a bad purchase - even as a windsurfing beginner. Let's get started.

Used sails

1. freeride sails - sails for the masses

Target group: Intermediate & advanced surfers, sporty surfers who don't necessarily want to win races; from water start to duck jibe, these sails grow with you.

Freeride is the golf class in windsurfing and is by far the largest group in our sport: subtly sheet in, glide off easily and cruise carefree over flat water. Maybe a little jump in between and a sleek jibe to turn round - that's freeride! Sails designed for this are one thing above all: uncomplicated, yet efficient and very versatile. They can do everything well - but are not specialists in any one area. Freeride sails are common in sizes 5.5 to 8.0 m² and are stabilised by five to six battens. Due to the deep profile in combination with a long boom Wave- and Free sailing the planing performance is improved. At the same time, however, the absence of camber (profile braces that support the batten on the mast and thus create a defined, rigid profile) maintains easier handling compared to freerace and race sails.

To keep the weight as low as possible, freeride sails consist of relatively large monofilm surfaces - and are only reinforced in special stress zones, for example in the camber area of the lower leech. Even though the current trend is towards skinny masts (also for larger sails), the freeride sails are still quite mixed - many sails can also be used with thick (SDM) and thin (RDM) masts. Masts set up. Don't be surprised if you don't find what you're looking for in the size range below 5.5 square metres for freeride sails. Here you are forced to resort to freestyle, wave or freemove sails.

2. freemoving sails - the all-rounders

Target group: intermediates, families; a sail for almost all sailing areas.

The sailing class of the Freemoving sail (mostly used in 5.0 to 7.0 square metres) has an absolute all-round claim without special suitability and therefore also many names that often refer to the same thing: Freemove, Crossover or Bump & Jump. With decent performance, the cloths - stabilised by five to six battens - should still offer similar speed and riding stability on the straight as pure freeride sails - but at the same time be more playful in the hand thanks to a slightly more manoeuvre-oriented cut and also withstand occasional wave use thanks to reinforcements such as grid materials and additional seams. Modern freemoving sails have largely been designed for skinny masts for around five years - the thin masts ensure a light and soft batten rotation, as is familiar from wave or freestyle sails.

3. wave sails - (surf) toys

Target group: Surf surfers and advanced manoeuvre surfers.

The first choice for anyone who wants to surf regularly in breaking waves. Thicker materials and reinforcements ensure that washes and crashes (usually) end without material breakage. Without wind pressure, they pull themselves quite flat, just as you would want when riding real waves. However, many are also suitable as strong wind sails for flat water. Wave sails well suited for advanced manoeuvre surfers. On the boom of a pure wave sail, a little more sensitivity is required in favour of agility to get it right in gusts or wind holes. Concepts with four and five battens are usually suitable for all-round use and are also well suited for flat water use in strong winds. Modern three-batten wave sails usually have a much more specialised design and are primarily designed for the demands of very good wave surfers who surf in large waves with an offshore wind. Regardless of size and concept, all wave sails without exception have been designed for skinny masts (RDM) for around ten years now.

4th freestyle sail - for trick specialists

Target group: Tricksters who are looking for crouching power moves.

Freestyle sail are now just as special as the moves they are made for. While only manoeuvre-oriented wave sails were used in the early days of the discipline, there is now a solid selection of special freestyle sails on the market. Until around 2010, most of these were still very similar in profile to wave sails. The only difference was that various reinforcements were omitted in order to save weight.

But when the trend shifted to power moves such as Kono, Culo or Burner, which require you to duck under the sail before jumping off, these became much more specialised - in other words, a completely flat profile without a disturbing life of its own was needed. Paired with a tight leech and wide Dacron panels in the luff, which soften the sails and ensure that a deep profile can be pulled tightly into the sail, which is neutral when unfurled. Common sail sizes are 4.0 to 5.6 square metres. These are stabilised by four to five battens and are invariably designed on skinny masts. The bottom line is that freestyle sails are specialists for use in combination with freestyle boards. Those who surf back and forth normally and perform jibing manoeuvres have a wider range of use with freemove, wave or freeride sails.

5th camber sail - supersonic windsurfing

Target group: Speed freaks and regatta riders.

Cambers are profile tongs that support the batten on the mast and thus create a very rigid and deep profile (even without wind pressure), comparable to that of an aeroplane wing. High trim forces on the luff give camber sails the necessary basic tension and stabilise the profile at the limit. The centre of effort thus remains fairly stable when overpowered, you can tease the maximum out of the sail size and convert it into pure speed on the right board with the right technique.

There are different concepts within the camber sail class: on the one hand, the high-end racing sails with seven to eight batten and three to four camber, which are built to be the first to cross the finish line. On the other hand, there are the more or less slimmed-down versions with only two to seven camber, six to seven batten and gradually more moderate basic characteristics, which go in the direction of freerace to freeride (only with a little more power and speed potential). The prerequisite for realising this theoretical increase in performance is a suitable board in the freerace or slalom category and a correspondingly higher level of riding ability. Because no matter how extreme or harmless the camber sail is set up, you have to make noticeable compromises in handling due to the camber and the wide mast sleeve (which absorbs a lot of water and therefore weight).

If you still have problems jibing safely, don't get on well with outboard footstrap positions (on freerace or slalom boards) and often need a little longer at the water start, you should steer clear of camber sails and prefer a normal freeride sail without camber. With a few exceptions, camber sails are designed for SDM masts.

6. sails for children and young people

Target group: Children up to approx. 13 years and under 50 kilos.

For children to really have fun, the smallest wave sail from mum or dad is not enough! It can quickly feel like 30 kilos in the hands of a child - if you simply put the weight of the material in relation to their body weight. For weight reasons, children's sails have no superfluous seams or reinforcements. They flatten out nicely without wind and are therefore very manoeuvrable. As the rigs have little basic tension, even light wind is enough to create a deep belly and thus propulsion. Components such as the mast and boom are designed for children's thin hands - it is therefore advisable to use complete rigs.

Under no circumstances should children's sails be combined with adult components. Common sizes are 1.0 to 4.0 square metres. These sails are made of either Dacron or mono film and are stabilised by up to three battens, depending on the size and area of use: if the sail is intended for beginners and light winds, one or two battens are always sufficient. A light aluminium mast is also absolutely sufficient. As soon as the sail is supposed to function in planing winds (>12 knots) - and the youngsters are practising trapeze surfing, water starts and planing, battening is important to stabilise the profile. Manufacturers usually equip such concepts with three battens and recommend a fibreglass or even carbon mast.

7. foil sails

Target group: Foil enthusiasts; use on foil boards.

Foil sails are specially designed for use on foil boards. There are now special types of foil sails for freestyle, for leisurely freeriding or for the regatta course. Despite all the differences, there are also similarities: Foil sails should be able to be pumped extremely well in light winds to support maximum early take-off. This is achieved by a soft sail profile and a comparatively straight mast bend curve. Foil sails also normally have no pronounced loose leech in the upper sail area, as active twisting and steam release is not necessary as with conventional windsurf sails. These special features of the sail design mean that you get more performance out of foil surfing, but most foil sails work less well or not at all on normal windsurf boards with a fin. So if you like foil and fin equally, you should stick with a conventional sail. If you are fully committed to foiling, you can opt for a special foil sail. Large foil sails for the regatta course are rigged on SDM masts, while the smaller, manoeuvre-oriented sails are mainly rigged on RDM masts.

Used masts

If you don't buy a new complete rig with the components recommended by the manufacturer from the same company, you are forced to delve a little deeper into the world of masts in order to find the right mast for your used sail. Here you are confronted with a multitude of data and figures. In the following overview, you can find out what is important for the purchase - and what you can safely forget:

RDM & SDM

RDM (Reduced Diameter Masts) are the modern, thin masts with a reduced diameter, often simply called skinny. Compared to its thicker predecessor, the SDM (standard diameter mast), it makes sails much easier to handle, more playful and therefore generally more user-friendly. They are also more stable against breaking loads due to their thicker wall thickness. The RDM came onto the market around 2004/2005. Nevertheless, the SDM has continued to prove its worth - thanks to its greater rigidity for large sails over 6.5 square metres and in performance-oriented regattas.

However, you can still find short SDM masts from earlier times on the second-hand market, which are designed for smaller sails. However, these hardly fit into a modern sail and are therefore almost worthless. "For example, I haven't sold a 430 SDM for a long time," says surf tester Frank Lewisch, who knows his way around thanks to his job in the shop, during the current test on Tobago. As a rough guide: sails between 3.3 square metres and 6.5 square metres, with mast lengths between 340 and 430 cm, are rigged entirely on RDM masts. Sails between 7.0 square metres and 9.6 square metres, with mast lengths of 460 to 490 cm, often need the thicker SDM. In the transitional range (especially with freeride/freerace sails), both are sometimes possible, but you should always follow the manufacturer's recommendations.

Mast length

The length must be correct. The English term luff refers to the length of the luff and is usually printed on the sail. The mast you want to buy should somehow match this luff length. Somehow because you have a certain amount of leeway. Masts are available in length increments of 30 centimetres (340 cm, 370 cm, 400 cm, etc.). As you always need a master extension for rigging, any intermediate length can be set. In our experience, however, masts should not be extended by more than 40 centimetres, as otherwise the sail becomes noticeably soft and performs less well. With a luff length of 440 centimetres, for example, it is therefore advisable to lengthen a 430 cm mast by ten centimetres instead of a 400 cm mast by 40 centimetres! The mast may only be too long if the sail has a vario top (adjustable webbing at the sail top) through which it can protrude at the top - this may then be up to 20 centimetres longer than the specified luff length.

With luff lengths of 432 centimetres, for example, there are often two mast lengths to choose from: a 400 with an extension of 32 centimetres or a 430 with an extension of just two centimetres. Two things should influence your purchase decision here. Firstly: Longer masts are always harder. The harder the mast, the tighter the sail feels. This can be an advantage for heavy riders (> 95 kilos), but in the hands of lighter surfers (< 65 kilos), the hard mast often means that the necessary profile is no longer pulled into the sail - a shorter mast would be more suitable in this case. Secondly, how does the mast fit in with the rest of your sail range? If you only have smaller sails anyway, you may not need a long mast at all. If you are planning to buy larger sails, you will need it sooner or later.

IMCS value

The IMCS value (IMCS = Indexed Mast Check System) is a relic from the past and is very limited in its informative value. It indicates the mast hardness - the lower the value, the softer the mast. However, as there are no differences in hardness within one and the same mast length (for example, all 400 masts have a hardness of 19, all 430 masts a hardness of 21, etc.), there is really no need to think about this value at all.

Carbon content

The higher the carbon content, the higher the quality, but also the more expensive the mast. A mast made of 100 per cent carbon is particularly light, but should be treated like a raw egg. Even small damaged areas can cause the mast to break as soon as it is placed under tension. You have to weigh up what you need and what your wallet can afford. In practice, masts with a low carbon content swing quite slowly when surfing (especially in choppy water), whereas high-quality carbon masts return to their ideal position more quickly - the sail feels lighter and more reactive as a result, and the surfer is also faster in theory. In practice, it is more a question of riding ability. Ambitious hobby surfers get a high-performance and still affordable product in the carbon class with a 50 to 80 per cent share - the compromises in performance and handling are hardly noticeable compared to the premium masts with 100 per cent carbon. For beginners (up to the first attempts at gliding), an inexpensive mast with 30 to 50 per cent carbon content is completely sufficient.

Hobby surfers get an affordable mast in the carbon class with a 50 to 80 per cent share.

Bending curve

If you are not sure about the bending curve, there is one important rule: the golden mean. The bending curve of masts is a tiresome and much-discussed topic in the windsurfing world. The various sail companies are not entirely innocent of this, as they all follow their own recipe for a successful combination of mast and sail and also want you to only combine products from their own brand wherever possible. Depending on how the mast bends, the profile of the sail changes and with it the entire sailing behaviour.

Some companies swear by a flex top, where the upper half of the mast is softer and therefore bends a little more than the rest. Others rely on the constant curve, which is characterised by an even, round mast curve. Last but not least, there is the Hard Top, where the mast is particularly hard in the upper section. Fortunately, in recent years more and more brands have switched to the golden centre of Constant Curve, which fits almost all brands and models quite well. So if you buy a mast that is not from the brand of your sail, you run the least risk of error with a mast that has the Constant Curve.

Check the condition of the sails

Recognise defects - and negotiate a reasonable price. In the following, we list a few points that you should keep an eye on when buying used sails.

Brittle mono film

The transparent plastic film called mono film, which most modern sails in the advanced range are made of, is light and does not warp, but is sensitive to creases and UV light. When buying second-hand, it is therefore not necessarily important how old the sail is, but how much sun it has been exposed to over time and how carefully it has been treated. If the mono film feels dry and brittle, is opaque to milky white, has many small creases and abrasion from sand, these are signs of reduced durability. If the film falls into the sail, it will quickly tear through over a large area. The Dacron cloth sails recommended for beginners and children are softer and less sensitive to creases and falls. It is also much more durable against UV radiation than mono film. A Dacron sail that is ten to 15 years old is therefore often still perfectly usable, whereas a monofilm sail of the same age is often not.

Replaced tracks

If a monofilm web between two seams (or battens) appears significantly clearer and lighter in colour, this is a pretty sure indication that it has been sewn in at a later date. If it has been replaced professionally and sewn cleanly, this is usually not a problem.

Open seams

Especially if sails are stored wet and rolled up for weeks or months, the seams can slowly soften. You should therefore check whether they are still sitting properly - or whether fluff is hanging over the sail like an old woollen blanket. Open seams in the foot area, below the boom, are a classic problem. Here, the sail is often pulled over the non-skid paint of the board, which can damage the seams.

Broken battens

Kinks and folds in the batten pockets indicate broken battens. If you are unsure, simply bend the batten a little and you will quickly realise whether it is still in one piece. Broken battens can be replaced relatively easily and do not have to be an exclusion criterion when buying a sail - but they are a good argument when negotiating the price.

Cracks in the mast sleeve

Cracks in the mast sleeve are often a consequence of mast breakage - or of frequent rigging on tarmac. Such a tear does not affect the sailing behaviour of the sail and is harmless up to a certain size (approx. ten centimetres). The problem is that it feels like it tears open a little further every time you rig it and at some point you can hardly thread the mast. This should be prevented as soon as possible with a patch or a seam from the sailmaker. If there are small tears: Press the price!

Stubborn stickers

On the second-hand market, you often come across seasonal sails from team riders who receive special conditions on new material from the manufacturer and therefore replace their sails every year. These are often covered with sponsor or event stickers. Firstly, you should check whether there are any dents or tears in the mono film behind the stickers, and secondly, you need to be aware that these things can be quite stubborn, depending on the adhesive. If the stickers are very adhesive and sit over graphics or seams, you may tear the seams apart when you try to remove them - or half the colour in the sail may come off with them.

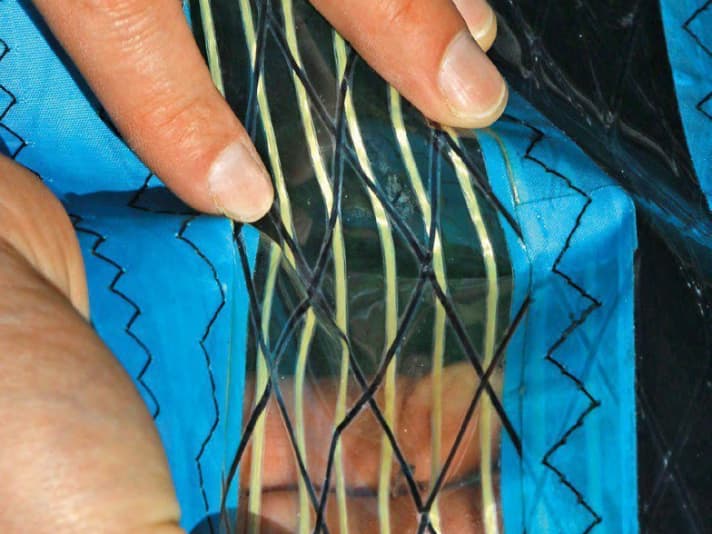

Ground camber

Over time, sediment between the mast and the camber can cause the roller blocks, on which the profile tongs run along the mast to rotate the sail, to rub off. Corners and edges grind into the plastic rollers and the camber no longer runs cleanly.

Check the condition of the masts

When buying used masts of any kind, it is always important to distinguish between signs of use and damage. A well-used, broken-in mast can last half an eternity under normal load. A brand new mast from the factory or a slightly damaged mast can split in two the first time it is rigged. Here are a few tips on what to look out for when buying.

Abrasion points

Especially in the area where the front piece of the boom grips the mast, abrasion marks are not bad and are unavoidable. However, if they are noticeably severe, this is a sign that the mast has been used a lot in sandy spots, where grains of sand get trapped between the mast and the quick release when rigging. In this case, it makes sense to mount your own boom and see if it still has enough grip on the worn spot. Corners, edges and furrows in the mast surface, on the other hand, are much more problematic because the mast can break there under tension.

Plug connection

If the luff is tensioned but the mast is not properly connected, cracks can quickly form on the connecting piece. Therefore, when rigging, you should always check that the mast has not slipped apart before tensioning. If the previous owner has not done this - and cracks have already formed due to misuse - these will continue to tear open until the mast breaks completely. Better not to buy!

Banana bender?

If sails are stored for a long time in the rigged state under downhaul rope tension, the masts slowly bend in the centre, in the area of the connector. The mast then loses tension over time and, in extreme cases, looks like a banana after one season. This can be more or less pronounced - a strong bend is often found in masts that come from a surfing centre. It is better not to buy these! So before buying, simply put the mast together and look at the bend with one eye. A minimal bend is not so bad, but the mast should not look like a banana.

Margins

At the edges at the bottom of the base, where the mast extension rests, and in the centre, where the two mast parts meet, the high pressure can cause damage such as small cracks and splintering at the edges over time. This is a sign that the mast has already been in use for some time - but depending on the extent of the damage, it does not have to be an exclusion criterion when purchasing. On www.surf-magazin.de under the search term "repair mast" you will find a workshop on how to repair this type of spot in an emergency.

Top cap

In the upper part of the mast, the plastic cap, which seals the mast at the top and presses against the sail top when tensioning, should still sit firmly in the mast and not move. If it falls out, the sharp edges of the mast can damage the mast sleeve the next time it is rigged.

Water in the mast

By shaking and listening, you can easily determine whether there is water in the mast. A wall on the inside of most mast tops is designed to prevent the mast from slowly filling up with water from below during longer swimming sessions and thus increasing in weight. If the top cap leaks slightly at the top but the wall is tight at the bottom, water will build up in the top section of the mast. The lower sections, on the other hand, are open at the bottom and are therefore safe in terms of accumulated water.

What prices are reasonable for used sails?

Previous year's models

With every model change (in one or two-year cycles), brand new sails are also flushed onto the second-hand market. Often from team riders, semi-pros or people with a connection to the windsurfing industry. Masts and booms are generally overhauled less frequently by manufacturers than boards and sails - so components that have only been ridden for one season are a rarity on the second-hand market.

Roughly speaking, you pay around half the list price for an undamaged sail from the previous year that has only been used for one season. The same applies to masts, if you can find one. A 4.7 wave sail from the previous year, for example, changes hands for around 450 euros.

Best Ager

Among sailors, best agers would be models that are two to four years old with normal signs of wear that are still up to date. To stay with the example of the 4.7 wave sail, you would have to factor in a good 300 euros for an undamaged model. In the case of more severe signs of use such as larger dents - or a replaced window, for example - the price is often only around 280 euros. Whether the sail is two or four years old doesn't really matter, it's more about how much sun, sand and salt it has seen. Large freeride or camber sails are slightly more expensive on the list, as they have often been used in more benign conditions and are still in pretty good condition after two to four years - accordingly, they are also priced higher. The price range for masts is generally enormous due to the different carbon content.

While you can sometimes buy a 50 per cent carbon mast in its prime for less than 100 euros, you can quickly pay three to four times that amount for a 100 per cent mast. Roughly speaking, best-age sails and masts are often sold for 30 to 50 per cent of the current new price.

Oldies

A tricky subject: sails that are more than five to six years old should generally be treated with caution. While you can still buy a well-maintained, six-year-old freeride board that came from a lake surfer without hesitation, you should be careful with sails. The materials simply become brittle more quickly over time - especially in the sun. Of course, regardless of the condition of the materials, a sail like this can still be a lot of fun and still work well with the right components - but only if it lasts. Realistically, you have to say that a piece of old foil, which you always have to assume will tear into pieces at the next touch (wash or catapult), is not really worth much.

Oldies that are still in one piece are sometimes traded for 80 to 150 euros. Old masts (especially short SDMs) fit poorly or not at all in most modern sails and are therefore often no longer worth much. They only make sense if you buy a matching sail from the same era.

In the third part of our second-hand buying series, we will tell you everything you need to know about buying additional accessories in Surf 6-2023 (on newsstands from 17 May 2023).